With Memorial Day—the unofficial start of summer—creeping up on us here in the States, I figure it’s time to thaw out the piece on “Calypso Fashion” that I put on ice last fall.

In the spring and summer of 1957, when calypso was in vogue, calypso was…well, maybe not in Vogue, but nearly everywhere else. In a March story about the coming flood, the United Press reported that “U.S. designers, going along with the calypso craze, are turning out everything from sports to jewelry in the styles and hot colors of the Caribbean.”1 American and Canadian department stores, especially, lost no time in promoting seasonal lines of “calypso” clothing. Their efforts often amounted to little more than dressing up pedal-pushers, espadrilles and Bermuda shorts in new names: “Slim-Jim” trousers would now be known as “Trinidadians,” revealed the UP, while so-called “Jamaica” shorts were “longer than briefs, shorter than Bermudas.” Generically “tropical” fabrics and motifs—khaki and seersucker, stripes and frills—prevailed. The tone of an INS wire story was more jaded, less gee-whiz: “‘Calypso’ looks pretty much like ‘Rhumba,’ ‘Matador,’ and other south-of-the-border fashion trends,” it shrugged.

For instance, a “calypso” outfit has to include a ruffled shirt, like last year’s popular matador shirts. Instead of a buttoned-up collar, however, “calypso” is worn lazily open. Sleeves are three-quarter length instead of wrist-length, and the ruffles are droopier.

“Calypso” ruffles can go any which way, not just up and down. You can stitch them to a scoop neckline or let them slide down the shoulder seam. The only requirement is that you have lots of them, preferably all over.2

Detail from the New York Times Magazine, 5 May 1942, p. 21. “The swirling folds of a calypso dancer’s frock are echoed in the red and white striped glazed chintz.”

While you wouldn’t know it from their hackneyed ad-copy (full of awful “calypso-ese” rhymes and blather about gay colors and carefree living), the fashion industry had actually done one or two dry runs before ’57. As early as 1942, in fact, in the wake of the first New York City calypso “boom,” the New York Times Sunday magazine ran a two-page pictorial surveying the work of New York designers who had turned the “vibrant tones that mingle on the Latin American palette” and the “richly imaginative native art and costumes of Mexico and Guatemala” into “a genuine source of fashion material” for North American women. As for the Caribbean in particular: it obligingly “sends us its lush colors. From the dancers whose feet patter in ceaseless rhythm we have taken the drape of skirts that sway to sinuous movements.”3 Keep in mind that this was a full two years before the invention of Chiquita Banana—though not before the “invention” of Carmen Miranda, obviously. The garish outfit supposedly available at Bonwit Teller (see photo at left) surely owed at least a small debt to the Brazilian Bombshell, although the more immediate inspiration may have been Judy Garland’s get-up in the previous year’s Ziegfield Follies, where, crowned with a bizarre phallic headdress, Garland sang the corny cautionary tale of Calypso Joe and “Minnie from Trinidad.”

While you wouldn’t know it from their hackneyed ad-copy (full of awful “calypso-ese” rhymes and blather about gay colors and carefree living), the fashion industry had actually done one or two dry runs before ’57. As early as 1942, in fact, in the wake of the first New York City calypso “boom,” the New York Times Sunday magazine ran a two-page pictorial surveying the work of New York designers who had turned the “vibrant tones that mingle on the Latin American palette” and the “richly imaginative native art and costumes of Mexico and Guatemala” into “a genuine source of fashion material” for North American women. As for the Caribbean in particular: it obligingly “sends us its lush colors. From the dancers whose feet patter in ceaseless rhythm we have taken the drape of skirts that sway to sinuous movements.”3 Keep in mind that this was a full two years before the invention of Chiquita Banana—though not before the “invention” of Carmen Miranda, obviously. The garish outfit supposedly available at Bonwit Teller (see photo at left) surely owed at least a small debt to the Brazilian Bombshell, although the more immediate inspiration may have been Judy Garland’s get-up in the previous year’s Ziegfield Follies, where, crowned with a bizarre phallic headdress, Garland sang the corny cautionary tale of Calypso Joe and “Minnie from Trinidad.”

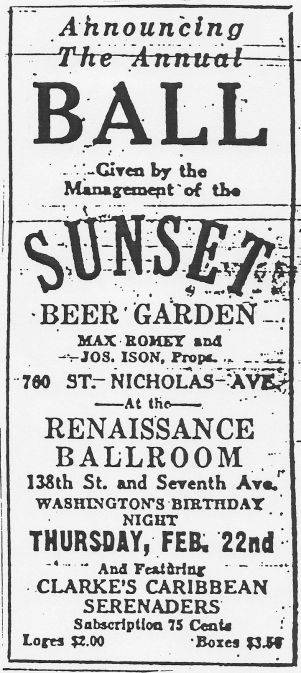

The clichés about tropical tones and sinuous frills persisted. In April 1945, as “Rum and Coca Cola” dominated the Hit Parade, Brooklyn’s Russek’s department store presented “Carry On at the Country Club in Calypso Casuals” as part of its “Suddenly Summer” fashion show at the Hotel St. Regis. (The “‘take it easy’ shirts and skirt dresses, influenced by the romantic costumes of the famous singers of Trinidad, were shown in Caribbean canary….”) The Seamprufe company, as I mentioned last fall (“Giving Calypso the Slip“), was already trying to get its “calypso colors” into women’s frilly things—er, intimate apparel—in 1949. SoCal’s “The Broadway” department stores reprised that campaign eight years on, with stockings that promised a “rich, riotous loot [sic] of sun and fun in color influenced by the Calypso craze.” “We borrow these happy tones from the West Indies,” Broadway’s admen explained, “and bring them to the sheer realm of hosiery.” In the realm of cosmetics, Max Factor hyped its new “CaLYPso Beat” lipstick as a “laughing color” of “happy character”: “It sways to a rhythm that’s excitingly sweet / Dances on your lips in Calypso Beat.” And while it concerned itself with curls, not frills, the Antoine Salon in Toronto, advertising its “Calypso Permanent” (“You’ll beat the drums for it”), promised a “magic Voodoo to the way our haircutters scissor this new cut that gives you the native loveliness of an Island beauty.”

Seamprufe’s visual motif of the barefoot, straw-hatted (and, need I point out? dark-skinned) troubadors serenading the elegant white lady from a safe distance also survived. It appears, for instance, in a 1955 ad for Saks Fifth Avenue (“Calypso Nights,” below), touting casual evening dresses by the Bermudian designer Polly Hornburg, a former fashion model and colonial culture-vulture who made her name selling “tropical” couture to the international jet-set out of her chain of “Calypso” shops in Bermuda and Jamaica. The daughter of one of the island’s top (Anglo) hoteliers, Hornburg set up her flagship boutique in 200-year-old slave quarters in the colonial capital of Hamilton. To quote Jamaica Kincaid: There’s a world of something in this, but I don’t have time to go into it right now….

Detail from New York Herald Tribune, 30 November 1955.

Two years later, in the midst of the Craze, those same stylized figures, all white teeth against dark skin, were beating out the “rhythm of summer” for Simpson’s department store in Toronto. (“Imagine the startling clarity of black and white,” the ad read, “…in staccato squares and gay polka-dots, against your suntanned summer skin…”)

(Toronto) Globe and Mail, 7 May 1957.

But well-heeled (white) women weren’t the only target audience for calypso-themed fashion. By 1957, it was mostly middle-class suburbanites who were being invited to enjoy—symbolically, anyway—the “light-hearted abandon” that typified the Islands, to answer their “irresistible invitation to lazy living” by donning a Marianne Blouse or a Calypso Sway Skirt. The call included black burghers, too, although their pitch had a slightly earthier spin: in a two-page “Modern Living” spread, Chicago’s Jet magazine, known nationally as “the Negro bible,” featured its cover girl modeling examples of the “calypso blouse, which has captured the fun, excitement and romance of a full-blown Caribbean carnival.” Its “frothy ruffles,” bare midriffs, and “air-cooled lacy necklines,” Jet glossed, were “all so typical of the carefree calypso life.”

Jet, 16 May 1957

Meanwhile, an ad in the teen-oriented Dig magazine tried desperately to appeal to young males with a figure that looked as if Ricky Nelson were torn between joining a barbershop quartet and the Lecuona Cuban Boys. “Hey, Mr. Tally-Man,” it suavely exhorted young hipsters, “don’ be a bu-bu. When daily-lite [sic] come down by the sea-side, be sure you’re siftin’ sand in the new A-1 Beachers” (the jean company’s latest clam-diggers). As for Dig-readers’ dads: a January 1958 full-page ad for Simpson’s encouraged male snowbirds “Going South” to buy Enid Mosier’s Hi-Fi Calypso LP and stock up on madras shirts, Dacron dinner jackets, and sport coats and Bermuda shorts in linen and space-age “Terylene.”

Children were thought to be especially susceptible to calypso’s call: even in 1955, “Calypso” playclothes were meant to satisfy the pre-teen’s demand for “copies of big sister’s styles,” while young boys in 1957, it was imagined, would find “Calypso” clothes “Crazy, man, crazy!”

Detail from Buffalo Courier-Express, 2 June 1957.

(Toronto) Globe and Mail, 1 March 1955.

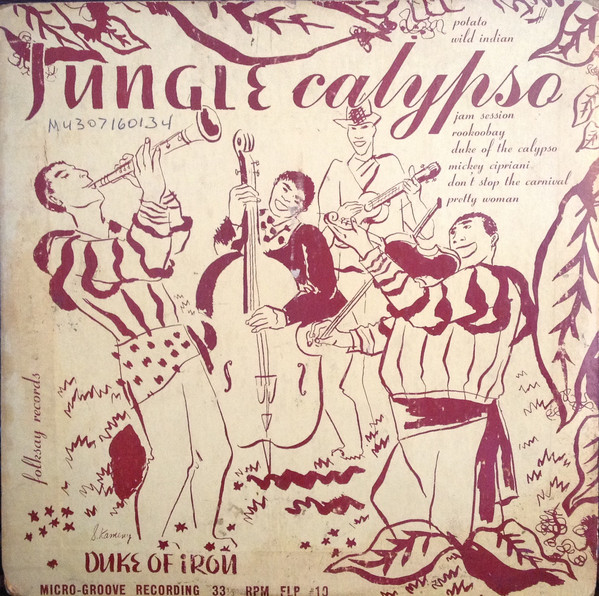

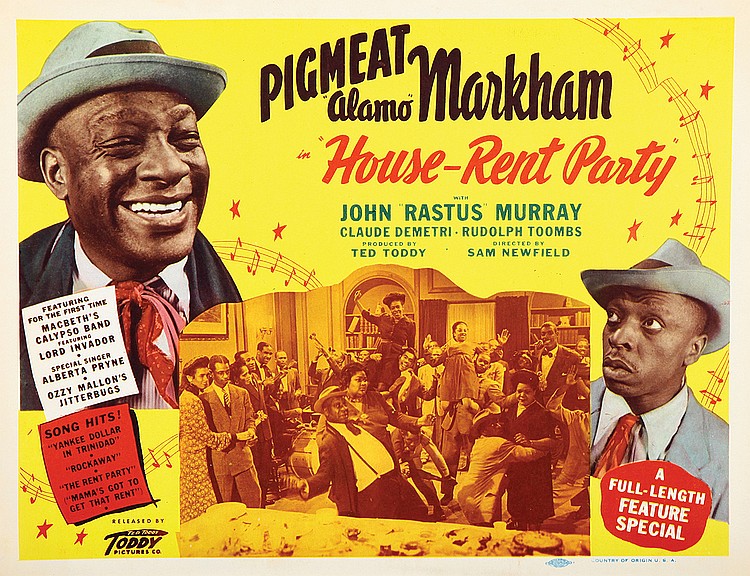

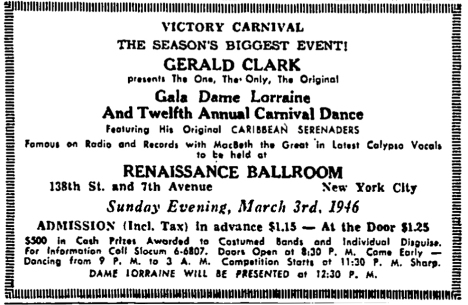

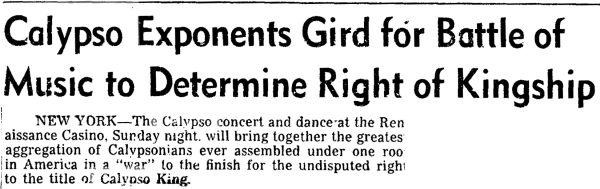

Where were the calypsonians in all this? The Duke of Iron, of course, had already sung about ladies’ lingerie. MacBeth the Great’s band had been hired occasionally to play for society fashion shows over the preceding decade; so had Duke’s. But while both men had plenty of sartorial flair, neither is known to have plugged “calypso” sportswear, say, or to have registered any opinion whatsoever about calypso-branded fashion.

Another natty dresser who dabbled in calypso did. Fred Astaire, who at the height of the Craze recorded the dismissively ironic “Calypso Hooray,” was interviewed by Richard Hublar for a profile in GQ, “The Astute Astaire“: “Asked about the so-called Calypso influence in sportswear, Astaire replied cheerily: ‘I sincerely trust that there is none whatsoever.’”

You can view more examples of Calypso Craze Fashion, including a full-color ad for Max Factor’s “CaLYPso Beat” and the ad described above for A-1 Manufacturing Co.’s “Beachers” pants, in the online preview for Bear Family’s Calypso Craze box set.

References:

1 Gay Pauley, “Caribbean Colors, Calypso Styles Form Latest Trend.” Schenectady Gazette 28 March 1957: 32. An abbreviated version of the story appeared on the Women’s page (“The Distaff Side”) of the Toronto Star (20 March 1957: 31) as “Calypso Craze Hits Fashion Designers.”

2 “Calypso Beat Is Taking Over In Styles As Well As Music.” Toronto Star 18 March 1957: 25.

3 Virginia Pope, “From Exotic Climes.” New York Times Magazine 5 May 1942: 20-2.