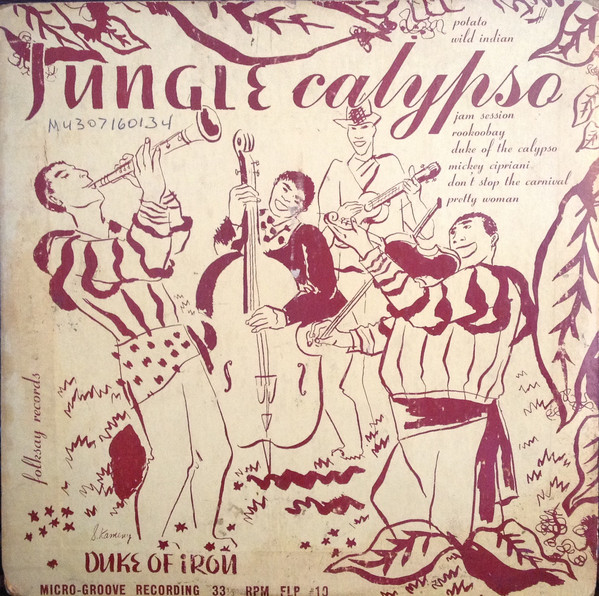

I meant to pass along this great tip from Lord Investor well before now. (His blog, by the way, is well worth your investment—far more profitable, to my mind, than…I donno…Bitcoin or Facebook or Blockchain or whatever other Newspeak-y thing is on everyone’s lips these days.) It’s a 1948 “soundie“—ancestor of the music video—of the Duke of Iron, voice and cuatro, with Gregory Felix on clarinet (and possibly Modesto Calderon on bass and Victor Pacheco, percussion), miming to their own recorded performance of “Wild Indian.” Why the lip-syncing, I don’t know, as the recording they’re singing along to is clearly not the one they made for Moe Asch in 1945. Perhaps because even though six sides from that recording session came out on Stinson in 1946, “Wild Indian” only saw the light of day when the album, Jungle Calypso, was re-released in 1953, with “bonus tracks,” as a 10-inch LP.

The “Soundies” era was mostly over by 1947, although old soundies were repackaged for television in the first decade of that medium, which probably explains the “Sterling Television Release” credit at the end of this particular video. (The film’s producer, Video Varieties Corporation, seems to have been in business at least through the early 50s. In recent years, an outfit called “Soundies Central” has repackaged a bunch of these old films for the web and DVD.)

Because they didn’t last—and, presumably, because they were only ever intended as a “throwaway” medium to begin with—not many have survived, so it’s really something when one turns up. (Kudos to Chris Lawson and Meloware Media for rescuing this one!) For our Calypso Craze set, Ray Funk got his hands on two from 1943 by Beryl McBurnie and Sam Manning, and Bear Family oversaw their restoration. One of these, “Quarry Road,” has since found its way to YouTube in a lo-res version.

I’ve heard of other calypso-related soundies. As I mentioned to his Lordship: when I was perusing old issues of Billboard some years ago, I came across a review of the Duke of Iron’s act at Manhattan’s Pago Pago Club in early 1941. The reviewer was annoyed by the fact that on the night he attended, the performance was interrupted by cameramen shooting movies of the entire troupe (which included Bill Matons, a/k/a The Calypso Kid, and his dancers, who had earlier done a record-breaking run with the Duke and Gerald Clark at the Village Vanguard). Elsewhere in the same issue, it emerged that two soundies of Matons, undoubtedly including the Duke, would soon be released by Spotlight Productions. Would love to see those. Almost five years later, when DownBeat ran a story about Lord Invader (who was in New York to pursue a lawsuit against Morey Amsterdam and the Andrews Sisters for stealing “Rum and Coca-Cola”), it mentioned that a short, “Yankee Dollar in Trinidad”—possibly a soundie of “Yankee Dollar,” which Invader was about to cut for Asch’s new label, Disc Records—would be released in early 1946. Never seen that one, either.

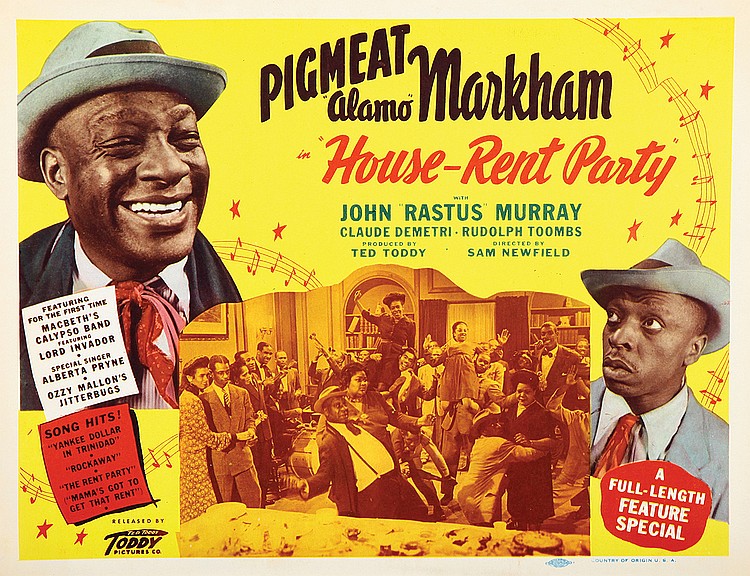

And of course the holy grail of calypso on celluloid: Lord Invader with MacBeth’s band in the 1946 Pigmeat Markham vehicle, House-Rent Party. You can see Gregory Felix, clarinet bell in the air, on the left side of the frame in that “proscenium” photo below. And to his left, behind the drummer: is that the Duke of Iron on cuatro? Another thought: maybe the “Yankee Dollar” short was just an edit from the feature film?

Anyway, “Wild Indian.” It’s possible the Duke himself wrote this, although like other resident calypsonians in New York, he wasn’t always scrupulous about attributing authorship. Today’s “Fancy Indian” carnival masqueraders are said to have evolved out of the “Wild” or “Red” Indians, which are among the oldest of Trini mas bands. (Cousins of New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians, no doubt, the Trinidadian versions are supposedly inspired by the Warao people of neighboring Venezuela, which is why the mas characters are sometimes known as “Guarahoon,” a word you’ll hear in the “nonsense” chorus of the song.) To the extent that Duke’s tune describes, enacts, and comments on carnival traditions—and implicitly, in this case almost proleptically, mourns their passing—it belongs to a genre that is the calypso equivalent of ole mas.