A note from Nonesuch Records that Gaby Moreno and Van Dyke Parks’s album ¡Spangled! (which will include last year’s single, a cover of David Rudder’s “The Immigrants”) would be out soon, together with a lucky score (on my annual visit to Portland, Oregon) of a mint copy of the reissue of Parks’s pan-and-calypso-ful Clang of the Yankee Reaper, prompt me to make my first post in over a year. The unrelenting horror of the current administration’s treatment of immigrants of color—all people of color, really—should have been the real motivation, I suppose. But it’s all too easy to lose sight of that particular horror against the backdrop of a thousand others, not to mention the steady thrum of poisonous rhetoric that aids and comforts Aryan nationalist terrorists with guns.

I’ve written before about Parks’s cover of Tiger’s iconic “Money Is King,” and so has my friend and collaborator Ray Funk, who in his semi-retirement has become a regular (and prolific) correspondent for the T & T Guardian. With his permission, and because the Guardian’s links tend to disappear capriciously, I’m sharing two of his recent pieces here. The first was occasioned by former Carolina Chocolate Drop Leyla McCalla’s cover of “Money Is King” on her album Capitalist Blues:

Money is King TG 22 June 19 (click that link to view the pdf)

(Here’s the official video:)

The other concerns (take a deep breath) Carlos Santana’s cover of a Calypso Rose tune, “Abatina,” written by Kobo Town’s Drew Gonsalves in answer to Roaring Lion’s 1938 calypso “Tina.” Santana’s version, retitled “Breaking Down the Door,” appears on his critically acclaimed comeback album Africa Speaks.

Here’s Santana, with vocalist Buika, performing “Breaking Down the Door” on the Jimmy Kimmel show:

Links to videos for Rose’s and Kobo Town’s versions are at the end of Ray’s feature (again, click the following link for a pdf):

Roaring Lion to Santana Trinidad Guardian 3 July 19

Two more bits of unrelated recent miscellany, in case another year goes by before I revisit this blog (!):

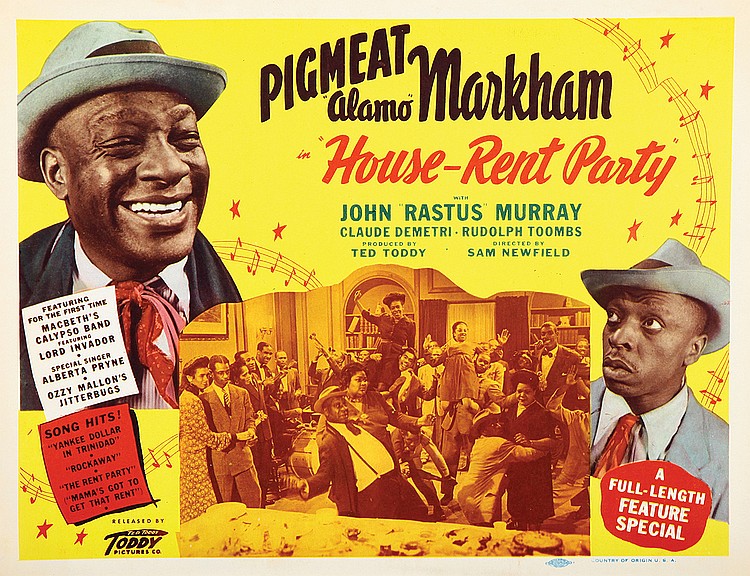

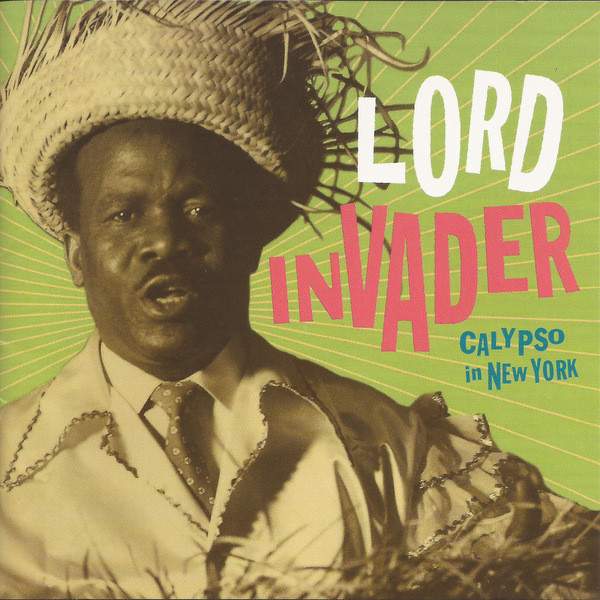

- Billboard reports that Smithsonian Folkways has completed its acquisition of the Stinson Records archives, which among other things will complement its collection of calypso recordings from Emory Cook and Moe Asch, with whom Stinson had a fraught relationship. (Complicated story.) Only a brief notice so far at the Smithsonian’s own website; we’ll hope to hear more soon.

- Documentarian Eve Goldberg has posted to YouTube her short film about Trinidadian-born piano virtuoso Hazel Scott, who was an enormous celebrity in the 1930s and 40s. It’s entitled (appropriately) “What Ever Happened to Hazel Scott?“