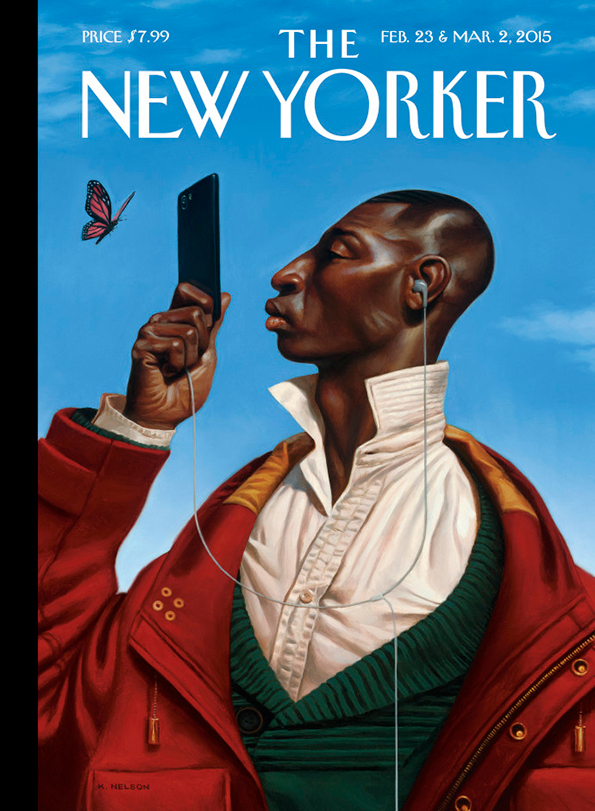

By strange coincidence, three institutions that played important parts in the spread of calypso in North America are marking big anniversaries this year—every one a good round multiple of ten: The New Yorker is 90, the Village Vanguard 80, and Radio Canada International 70. I hope to post about all three before the year is out, and today I start with the eldest.

For calypso researchers, The New Yorker is famous for one thing: “Houdini’s Picnic,” a profile of Wilmoth Houdini, the self-crowned king of New York calypsonians, that appeared in the issue of May 6, 1939. Its author, the legendary Joseph Mitchell, had recently joined The New Yorker as a staff writer after a star turn at the World-Telegram; “Houdini’s Picnic” was one of his earliest pieces for the smart-set weekly. It’s a classic of its type: part character sketch, part urban chronicle—a type that, as it happens, Mitchell practically invented. “He was drawn to people on the margins,” comments Charles McGrath, reviewing a new biography of Mitchell: “bearded ladies, Gypsies, street preachers, Bowery bums, Mohawk steelworkers, the fishmongers at the Fulton Market.” But his tone is mostly curious and sympathetic. A “great noticer” and a “careful listener” with a superb ear for dialogue, Mitchell was a sociologist at heart, “genuinely interested in his subjects as human beings, remarkable because they so vividly demonstrate that one way or another we are all a little weird.” There is “no kitsch in his portraits,” adds current New Yorker editor David Remnick, introducing Up in the Old Hotel, the definitive collection of Mitchell’s writing for the magazine. By contrast, the Journal-American‘s H. Allen Smith, like many of Mitchell’s rivals and imitators, saw people “as ‘characters,’ and mined them for their colorfulness” (McGrath again). Smith’s portrait of Houdini, “Hot Dogs Made Their Name,” which appeared a year later (and was collected in Low Man on a Totem Pole), is arch and condescending. Where Mitchell is deadpan, Smith is jokey. Mitchell’s Houdini is rough-edged and well-spoken. Smith’s is a buffoon.

For calypso researchers, The New Yorker is famous for one thing: “Houdini’s Picnic,” a profile of Wilmoth Houdini, the self-crowned king of New York calypsonians, that appeared in the issue of May 6, 1939. Its author, the legendary Joseph Mitchell, had recently joined The New Yorker as a staff writer after a star turn at the World-Telegram; “Houdini’s Picnic” was one of his earliest pieces for the smart-set weekly. It’s a classic of its type: part character sketch, part urban chronicle—a type that, as it happens, Mitchell practically invented. “He was drawn to people on the margins,” comments Charles McGrath, reviewing a new biography of Mitchell: “bearded ladies, Gypsies, street preachers, Bowery bums, Mohawk steelworkers, the fishmongers at the Fulton Market.” But his tone is mostly curious and sympathetic. A “great noticer” and a “careful listener” with a superb ear for dialogue, Mitchell was a sociologist at heart, “genuinely interested in his subjects as human beings, remarkable because they so vividly demonstrate that one way or another we are all a little weird.” There is “no kitsch in his portraits,” adds current New Yorker editor David Remnick, introducing Up in the Old Hotel, the definitive collection of Mitchell’s writing for the magazine. By contrast, the Journal-American‘s H. Allen Smith, like many of Mitchell’s rivals and imitators, saw people “as ‘characters,’ and mined them for their colorfulness” (McGrath again). Smith’s portrait of Houdini, “Hot Dogs Made Their Name,” which appeared a year later (and was collected in Low Man on a Totem Pole), is arch and condescending. Where Mitchell is deadpan, Smith is jokey. Mitchell’s Houdini is rough-edged and well-spoken. Smith’s is a buffoon.

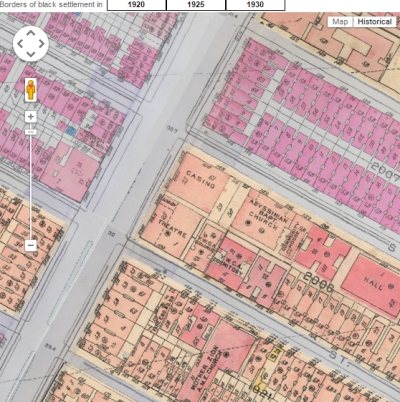

Joseph Mitchell wasn’t the only one of Harold Ross’s staff writers to cast an interested eye upon New York’s West Indian community. As early as 1928, “The Talk of the Town” took an excursion to Van Cortland Park in Riverdale—er, the Bronx—to look in on the “group of West Indian Negroes” who congregated there on Sunday afternoons to play “an unusually beautiful game of cricket” (and speak an equally “beautiful brand of English”). (J.M. Flagler would return in 1954 to write a long profile of West Indian cricketers in New York, “Well Caught, Mr. Holder“; Edith M. Agar and Brendan Dealy checked in once more in 1988.) In the course of keeping up with “Exotic Harlem,” meanwhile, Pauline Emmet in 1930 schooled herself on West Indian-American cuisine: “The West Indian Negro…will scarcely look at a chicken,” she pronounced. “What he likes are yams, yucas, papayas, and things like that.”

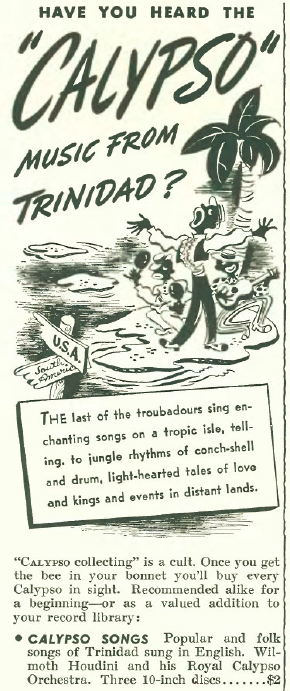

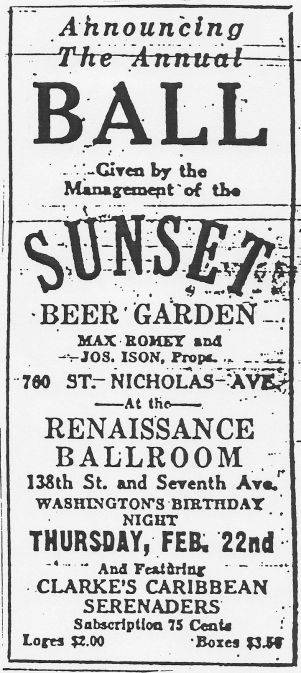

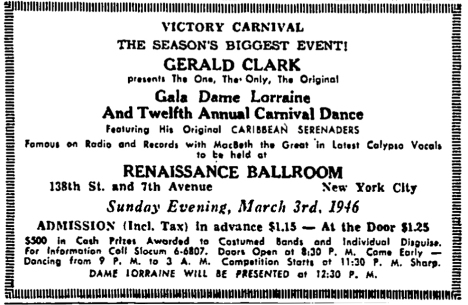

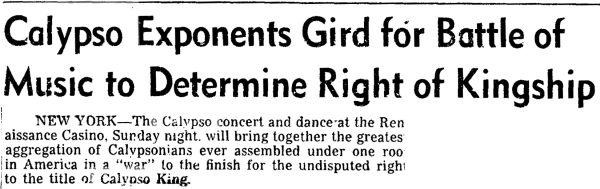

And music? As I mentioned last month, it’s a safe bet that the Renaissance Ballroom’s house band, led by Vernon Andrade, wasn’t only supplying swing tunes for the 5000 masquerading Lindy Hoppers and Suzy-Q’ers at the West Indian “Coronation Ball” that Earl Brown visited in 1937. By December 1938 the magazine’s anonymous popular record reviewer, always abreast of emerging trends, was recommending “selected West Indian discs” as a last-minute Christmas gift for “friends who will be diverted by the curious rhythmic outbreaks in dialect from the Calypso singers.” He began with a representative five, but as Decca had already issued “almost a hundred of these native naïvetés,” some of which seemed “shrewdly manufactured for the tourist trade,” he referred “Calypso collectors”—they were a thing—to midtown’s Liberty Music Shop for “[e]xpert first aid.” By the following year, Steinway & Sons Record Shop, also in midtown, was advertising its own recommendations…

…and Houdini was back on the radar of the magazine’s unnamed reviewer, who led off his December 30th column with a notice for the album advertised above, Houdini’s—and calypso’s—first. (Heretofore, he explained, “Calypso songs, by which the natives of Trinidad comment informally on whatever events of the moment strike their fancy…have been casually released on single discs.” But they have “caught on so successfully during the brief time they’ve been available in this country that now Decca has come out with a three-record set.”)

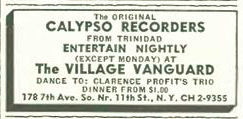

When calypso began to be featured at Cafe Society and the Village Vanguard in the summer of 1939, it naturally showed up in “Goings On About Town,” and eventually the Vanguard even took out small ads:

In 1941, Robert A. Simon was amused by the calypso that Belle Rosette (Beryl McBurnie), who had debuted at the Vanguard in December 1940, sang at one of Louise Crane’s high-concept “Coffee Concerts” at MOMA—a “South American Panorama” that also featured Elsie Houston, the Grupo Incaico, and a Haitian “Rada” group. (“Some of the visitors may have expected terribly primitive revelations,” quipped Simon, “but the event was no more aboriginal than a good floor show.”) Belle Rosette’s offering “began with international topicality and ended with something about Bach and Toscanini discussing Calypso music.” If that report seems a tad flip, then Simon at least conceded, after a lame attempt of his own, that “manufacturing Calypso lyrics isn’t so simple as one might expect.”

Houdini’s swan song for The New Yorker was in 1944, when he made an uncredited cameo in an ad for Bell Telephone, which had begun overseas long distance service to Trinidad earlier that year (and nicked the image in the lower lefthand corner from the cover of Houdini’s above-mentioned album for Decca). Note the nod to the “Good Neighbor” policy.

The last New Yorker writer to engage with New York’s West Indians in a spirit akin to Mitchell’s was J.M. Flagler, who twice in the mid-50s called upon cricketer, Con Ed clerk, and amateur composer Joseph Willoughby as his native informant: once to comment on the West Indian Day Parade, then held on 7th Avenue in Harlem, and again to weigh in on the 1957 Calypso Craze. On the latter occasion Willoughby, who with his partner, Harlem M.D. Walter Merrick, wrote “Run, Joe,” a 1947 hit for Louis Jordan, was equivocal: “On the one hand, I stand to profit personally,” he conceded, as his songwriting services were once again in demand and three recordings of his older calypsos had been reissued. “On the other hand, I fear that the cause of calypso is not being well served artistically.” Make that cricketer, clerk, composer…and diplomat.

In more recent years, the keen and versatile Hilton Als, who joined The New Yorker in 1994, and who, in the words of Coco Fusco, was reared in Brooklyn “by uppity Caribbean matriarchs,” can be counted on periodically to shed light on things West Indian and West Indian-American (“Notes on My Mother,” excerpted from his memoir, The Women, is an early example)—although it was Ian Frazier who wrote on the Brooklyn Labor Day j’ouvert parade back in 2010.

Kadir Nelson’s cover—one of nine—for the 90th Anniversary issue of the New Yorker (via the It’s Nice That blog). Any chance Eustace has some classic calypso loaded on that smartphone?